The first photo of Molly I ever took.

She had been suffering from some minor health issues for several months, but two weeks before she died things got a bit worse, and then dramatically so. On June 6th we thought we had a handle on things; we knew she was diabetic and that she would need special care going forward, but she also hadn’t been eating or drinking very much and was losing weight. I asked the vet to monitor her blood glucose for the first day of her treatment so that we would be guaranteed to get her requirements right. The insulin worked, but the vet was concerned that Molly didn’t appear to be doing well otherwise, and asked to keep her overnight. On the morning of June 7th I got called to the vet’s office. Around noon we were told that Molly’s condition had worsened significantly despite her responding well to insulin treatments. Her heart was failing, there was fluid in her chest, her kidneys were likely also failing, and she now had to be force-fed with a syringe. There were a few tests left that might have given us a firm diagnosis, but the prognosis for all the potential diagnoses was a painful death from heart failure sometime in the next few days or weeks. We took Molly home. About twenty-four hours later the vet came to our apartment, and Molly passed away peacefully in my arms. She was, we think, fifteen years old.

Molly in my mother’s backyard.

That night I fed her chicken, which she refused to eat, and made a makeshift litter box from a Rubbermaid bin I emptied out and some shredded newspaper, which she refused to use (though she didn’t use anything else, either). From the condition of her fur and so on I guessed that she had belonged to someone, but that she’d been out of doors for a while. She looked in decent health, but was dirtier than well-cared-for outdoor cats generally are. Later, a vet would tell me that she was at least a year old when I found her, but could have been as old as three. Abandoned and abused cats were not a rare find in the neighbourhood at the time, so when the stores opened the next day I bought cat food and a proper litter box. I also took some photos of the cat and put up posters around the neighbourhood, on telephone poles, on the community bulletin boards at the convenience stores, that sort of thing. Two people came to look, but both said she wasn’t their cat.

After a while I realized that nobody was going to claim this cat, and my options were turn her over to a shelter or keep her myself. Julianne, my girlfriend at the time, worked for a farm where the excess cats from the local shelter were kept, and I was not impressed. The care they received was mostly a form of benign neglect, and they were sometimes picked off by coyotes or trampled by livestock. And I’d heard stories of other things that, while not actually harming the cats, were not things I thought were acceptable. Julianne did what she could to make it a better place for the animals, but one person with no real authority can only do so much. I decided to keep the cat.

I wasn’t the one to name Molly. I remember there being conversations around naming her, but I don’t remember any of the other names that were proposed, only that Julianne was the one to suggest “Molly,” and that it seemed right. My memory of those days is fuzzy; not only was it a long time ago, I was living in extreme poverty—these were the days when my grocery budget was roughly twenty dollars a month—and my health was deteriorating pretty rapidly. I know that it took Molly a long time to be comfortable with me picking her up, but that she was otherwise extremely affectionate and chatty. She liked to spend time in window sills, and my landlord, who lived above me, said that she would sit in the window and cry for a good half an hour after I left the apartment.

Molly amongst her toys.

March of 2005 was a tough month for me. Julianne and I split up after seven years in circumstances that at the time seemed very dire, I dropped out of graduate school, and was so poor that I was going to lose my apartment and would have to move back in with my mother in Waterloo. I was in counselling for stress and severe depression. On top of that I got very, very sick with a respiratory illness of some kind (probably not SARS, but it was the right time and place, and the symptoms were very similar; I was just too stupid to see a doctor) and lost something like fifteen pounds over the course of a weekend. All of these events happened in the span of about ten days. There are people who would and did suggest that I shouldn’t have been allowed to have a pet at all under those conditions. While I understand where that argument comes from, my response to those people today is identical to my response then: go fuck yourself.

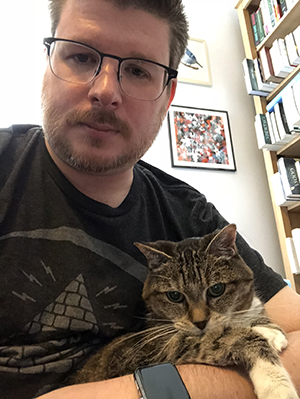

Molly and me.

Molly in the grass.

Molly saved my life. It wasn’t that she meowed at the right moment, or rubbed against me and knocked the knife away or anything dramatic like that. She was my companion, and just as importantly, maybe more importantly, she was my responsibility. I don’t think it’s possible to exaggerate how much Molly as a responsibility was important to my survival. I knew there were people who loved me, though it was good for me to hear it when I called my sister. But what I needed most was to know that I was needed in a literal way. I had friends, and I knew they would mourn. But Molly, who was just a stray cat I’d had for less than eight months, who was a life so small she wouldn’t matter at all to some people, might not survive without me. And that was enough. It was more than enough. Molly saved my life just by being in it.

Molly in her bed.

I went to northern Saskatchewan for three and a half years to build power lines while Molly lived with my mother. I saw her only a few days a month in that time, and the guilt was intense. The job was stressful, but it allowed me to pay down my debts and save some money. Last August, Molly and I moved back to Toronto, and my girlfriend Jess moved in with us in October. My health still isn’t good, but my chronic issues are under control. I have a more or less stable job at a reasonable wage, and some money in savings. I love and am loved, and my home is filled with books and art and other things I enjoy. I wanted very much to make this place a good home for Molly, to repay her for all those years we lived in poverty, and for all those years I left her alone while I worked in the north. She lived here for less than a year before she died, and many of the plans I had for making this space better for her were left unfinished.

When we brought Molly home from the vet we decided to fill her final day with all the things she loved. She was better at home than at the vet’s office, but it was clear that she didn’t have much time left. She was weak, and had trouble walking and keeping warm. Molly was always a decorous cat, who showed shame when she wasn’t clean, and it was hard to see her unable or unwilling to groom herself, and unable to make it to the litter box without help.

Molly and I watching bird videos.

Molly on the bed her last night.

I took Molly outside again, to the front yard this time, and she ate some blades of grass, the first thing she’d eaten voluntarily in days. She seemed, briefly, happy. We pet her, and brushed her, and let her lay in the sun.

A few hours later the vet and her assistant came. I don’t want to relive the whole thing here, although right now I’m seeing it over and over again in my head. I held Molly in my arms from the time they arrived until they left with her body. Jess was braver than I was, and dealt with the vet for me. She asked the questions, and worked out the logistics, and did all the things I couldn’t. I didn’t want to let go of Molly. I told her over and over again that I loved her. I told her that she saved me. I thanked her for all she had done from me, and I told her I was sorry I wasn’t able to do more for her. About two in the afternoon, Molly died in my arms.

Molly on the front lawn.

It was more than a week before I could take her water dish from its spot. I even found myself refilling it. There were times over the last fourteen years when I was so poor that I had to make a choice as to whether I would eat, or the cat would. The cat always ate. And no matter how poor I was, no matter how bad things got, the rule remained: the water bowl must always be full. It is so hard to let go of these ways of being. I’ve found myself halfway out of my seat to look for Molly more times than I can count. I had to move things around the apartment because out of the corner of my eye, if the light was right, they looked like her. We bought houseplants. I didn’t think I was the sort of person who would want to have a pet’s ashes, but we have Molly’s in a little cedar box with her name engraved on it, and I derive enormous comfort from that little box. I find myself touching it several times a day, and just as hugging the cat was the first thing I used to do when I got home from work, now I feel compelled to place my hand on the box. I long to hear the chirping noise she would make at least one more time, but I never thought to get it on video. I thought I would have more time. There have been so many moments when her absence has hit me like it’s just happened, and it’s a feeling of loss so profound I will sometimes mistake it for panic. People will sometimes say that pets are part of the family, and I truly believe that: they are not children, or siblings, or parents; they have their own, unique place in the family unit, and the way they are bound to us and we to them is also unique. Molly was, in that sense, my family. My story for the fourteen years she was in my life is also her story, and hers is mine.

There is so much more I could tell you: about how much she loved to eat fish, about how she hated other animals, about the time she fell out of a window and landed on my face. About how she loved to have her front legs scratched, and how for years she always wanted to sit in my lap, and then for years she didn’t. I could tell her story for thousands of more words and still not be finished. She was my family, and there will always be more to say.

The last photo of Molly ever taken.

Molly’s ashes in the little cedar box.

2 Comments